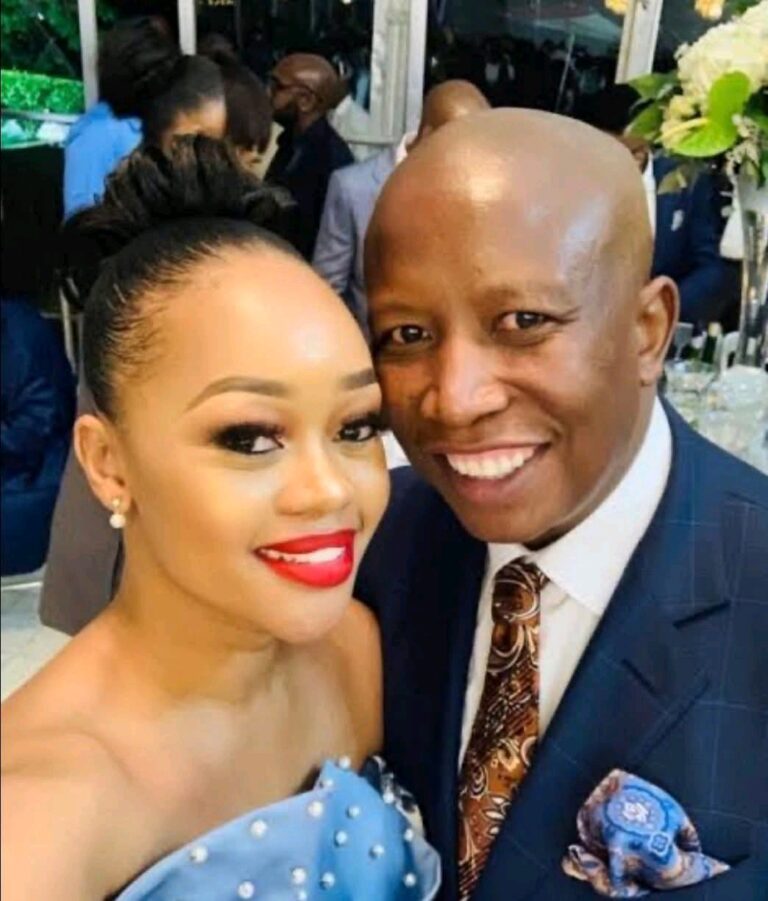

Breaking generational cycles and redefining the value of domestic work in South Africa, Dr Thobeka Ntini-Makununika’s remarkable story is one of courage, resilience, and academic excellence. Recently graduating with a PhD from the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), Dr Ntini-Makununika has not only earned her place in academia but also given a voice to the many women who have walked the path she once did.

Coming from a lineage of domestic workers, Dr Ntini-Makununika represents the third generation in her family to engage in this line of work. Both her late grandmother, mother, and aunt worked as domestic workers, and she too followed the same path in her early life. From the age of 13, she worked part-time for white families and at holiday resorts in KwaZulu-Natal, giving her firsthand experience of the complex relationships between domestic workers and their employers.

Her PhD thesis, titled “Unravelling the Dynamics of Power in the Employer-Domestic Worker Relations in Contemporary South Africa, KwaZulu-Natal: Praxis-Oriented Research”, explores the deeply rooted power dynamics between domestic workers and their employers. The study challenges longstanding societal perceptions of domestic work and delves into the colonial, patriarchal, and racial histories that continue to shape these relationships today.

“I wanted to humanise domestic work, redefine its societal value, and inspire reflection and action. It’s a call to reconsider whose labour we honour, whose voices we centre, and what justice truly looks like,” said Dr Ntini-Makununika.

One of her most powerful findings was that exploitation within domestic work often transcends racial boundaries. Surprisingly, several domestic workers she interviewed shared that their worst experiences came from working for Black employers. This insight underscored that the inequality in domestic work is not just about race, but also about class, social status, and internalised oppression.

Dr Ntini-Makununika also noted that while employers were clear about their own working hours, they were often dismissive or vague about the working conditions of their employees. “It signalled a devaluation of their employees’ time,” she reflected.

Her research was participatory in nature, grounded in real-life dialogue, and revealed that domestic workers often saw themselves as powerless due to years of marginalisation. However, through engaging conversations, many began to recognise their agency and small acts of resistance within their roles. Even employers showed moments of vulnerability, leading to greater mutual understanding.

The academic journey was not without its challenges. Working at the University of Zululand, a historically disadvantaged institution, exposed her to systemic inequalities, shaping her academic voice. Balancing work, research, and personal commitments required immense discipline and emotional resilience, especially when faced with stories of unpaid dismissals and subtle racial aggression.

For Dr Ntini-Makununika, the journey was not just academic—it was personal. “I wasn’t writing just for academia. I was writing for the daughters of domestic workers who may one day read my work,” she said.

She concluded with a powerful message: “Until we value the hands that clean our homes and raise our children as much as those that govern boardrooms, we will never dismantle the inequality woven into the fabric of our daily lives. Domestic work is work. Let’s ensure it is decent work.”

Dr Thobeka Ntini-Makununika’s achievement is not just her own; it represents hope for many who dare to dream beyond the limitations society places on them.