A shocking expose of alleged corruption at the highest levels of South Africa’s law-enforcement system unfolded this week when murder suspect Vusimuzi “Cat” Matlala delivered bombshell testimony before Parliament’s Ad Hoc Committee on police corruption. Matlala, currently detained at Kgosi Mampuru Correctional Centre, made startling claims that implicated former Police Minister Bheki Cele, senior law-enforcement officials, and even major financial institution First National Bank (FNB).

The Ad Hoc Committee was established in October to investigate systemic interference in criminal investigations, following explosive allegations from Lieutenant General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi. Mkhwanazi previously accused senior politicians and top police officials of sabotaging sensitive investigations into politically linked killings, particularly in KwaZulu-Natal. He alleged that the disbanding of the Political Killings Task Team at the end of 2024 was a deliberate move to shield Matlala and other powerful individuals from facing justice.

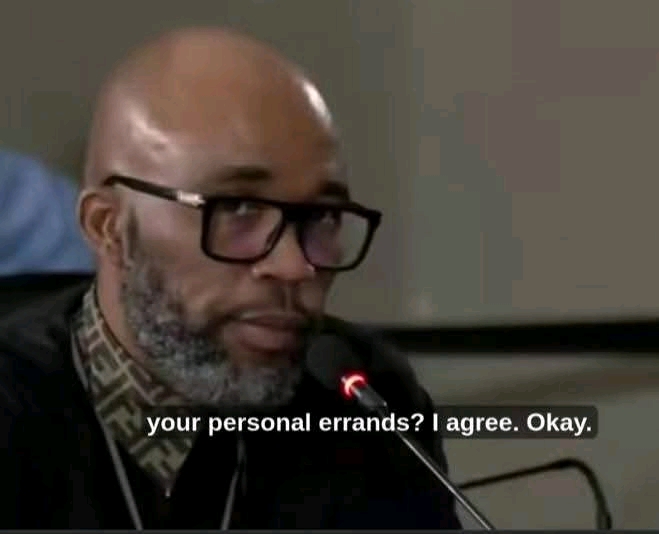

Matlala’s testimony intensified those concerns. Responding to ANC MP Thokozile Sokhanyile, who questioned whether the handling of large cash withdrawals constituted money laundering, Matlala boldly suggested that the bank, too, should be held accountable.

“If it’s money laundering, then why did FNB allow us to withdraw the money? Maybe they should also be charged,” he said.

He claimed he had instructed his sister to withdraw R300,000 from FNB—money he later collected from her before carrying it back to his Menlyn penthouse in a Woolworths shopping bag. According to Matlala, this was part of a R500,000 bribe paid to Cele, who he says had initially demanded R1 million. The alleged payments were made in two instalments: R300,000 and R200,000, both handed over in Woolworths bags.

Matlala alleged that Cele accepted the payments in exchange for halting raids on his properties and stopping ongoing SAPS harassment. He described an aggressive December 12, 2024, raid on his Waterkloof Ridge home, where masked SAPS officers stormed the residence in the early morning hours, forcing his family—including four of his children—to lie on the floor. He claims Cele directly intervened to stop further raids after receiving the bribe.

These claims directly contradict Cele’s earlier statements denying any involvement or personal connection to Matlala. Yet Matlala told the committee that Cele frequently visited and stayed at his Menlyn penthouse, raising further questions about their relationship.

Matlala faces multiple serious charges, including conspiracy to commit murder and attempts to capture senior police officers. However, his testimony has opened new debates about corruption networks that may span political circles, policing structures, and even private institutions such as banks.

The allegations suggest a deeply entrenched system where political power, criminal interests, and financial channels may have worked together to protect illicit activities. As the committee continues its inquiry, the pressure mounts for accountability, transparency, and answers. South Africans now await clarity on whether the claims will lead to criminal charges—and what this means for institutions tasked with protecting the nation.